The Frith Stool stands in the middle of the Quire at Hexham Abbey, a solid block of sandstone that was broken in two during the 19th century and cemented together again; the stone has been worn smooth by human hands over many centuries. It was made into a seat in the earliest days of the church, probably in the 7th century, and it has played a part in its story ever since.

Perhaps Saint Wilfrid had this stone seat made soon after he founded the first monastery here about 674. Wilfrid was copying the stone churches that he had seen when he stayed in France, on his journeys to and from Rome. He was much impressed by the splendid buildings and political power of the Church in Merovingian Gaul, and he would have seen there stone and wooden seats like this one, where bishops and abbots sat presiding over their teams of clergy. When Wilfrid founded the first church at Hexham he was Bishop of the Northumbrians with his seat at York; but later he became abbot and bishop here at what was then known as the Hagustaldian Church, so almost certainly he sat on this as his throne; with, it is to be hoped, a cushion. Hexham was a cathedral, at the centre of a diocese, from about 678 to about 821, and this throne was perhaps made the bishop's official cathedra.

Wilfrid used stones brought from the Roman ruins at Corbridge for his church, and this large block of stone too may have been quarried originally by Roman workmen. Probably Wilfrid's own Anglo-Saxon Northumbrians scooped out the seat and carved the simple patterns on the arms and front. There parallel straight lines to emphasize the outline of the seat, and an interlace design on the upper side of the arms ending in a triquetra. The same pattern appears in a manuscript illumination of St Matthew seated in a wooden chair that was painted at Canterbury perhaps about 750; but the design is so simple that it could have been carved at almost any time. The seat seems to have been set against a wall, in the middle of stone benches for other clergy; and perhaps it was once on stone supports carved in animal form, rather like larger versions of the beasts now in the niches of the nave.

In later centuries Wilfrid's monastery fell into decay, though the church continued in use and the hereditary priests who served it may have sat where bishops and saints had sat before them. In the 12th century the Norman Archbishop of York sent Augustinian Canons to revive the church and restore its former splendour. They rebuilt in the new Norman style and, when fashions changed, in the Early English form of Gothic, so that nothing of the earlier church was left above ground; but they treated with great respect the ancient chair, for it undoubtedly went back to the days of the saintly founders and it had been sanctified by a great many holy bottoms. Prior Richard, who led the new community in its early days and was the first historian of Hexham, wrote of it with pride, calling it the FRITH STOOL.

The Frith Stool was ‘the Chair of Peace’. Frith, though now obsolete, was common enough in Prior Richard's time and long before, in Anglo-Saxon English and Old German, meaning peace, security and freedom from molestation. Different forms of the word are found in the name ‘Frederick’ (peace-ruler) and the modem German words for peace, Friede, and churchyard, Friedhof. Many of the greater churches had such frith stools placed, as was this one, close by the high altar. Refugees in time of trouble and civil war, or wrongdoers in flight from authority and justice could claim the protection of the Church until they were assured of a full and fair trial. Anyone breaking the right to sanctuary by taking or killing a refugee within the church was liable to a fine of £96; but, writes Prior Richard, if the victim reached ‘the stone cathedra next to the altar, which the English call the fridstol ’, that breach of sanctuary was beyond pardon, and the culprit faced excommunication or death.

The Frith Stool remained close by the high altar throughout the Middle Ages, and it was certainly used in the troubled times of the Border Wars, though we cannot be sure just how much safety it guaranteed. Deserters and petty thieves found their way to the protection of the Priory Church and became ‘grithmen’. In Edward III's reign, the king authorized the recruitment of such wrongdoers into the army. In Tudor times the right of sanctuary was strictly limited, for Henry VIII would allow no one to defy the royal law; and it was completely abolished soon after. The Frith Stool became redundant, a heavy and awkward piece of unwanted furniture. It was moved wherever it was least in the way, to the north aisle, the south transept, and back to one side and then the other of the high altar; it was probably during one of these moves in 1830 or 1859 that it was broken and badly patched up.

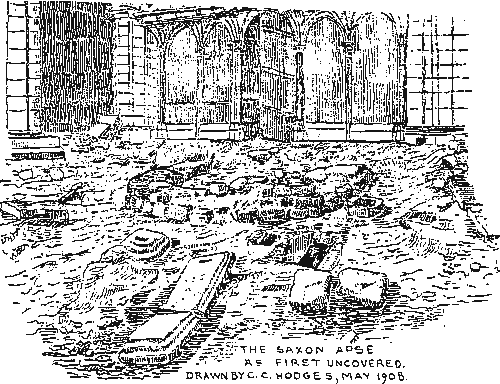

In May 1908, when the new nave, was completed, work began to re-arrange the Quire and to relay its whole floor. C C Hodges and J P Gibson then uncovered foundations of the apsidal east end of a Saxon church, with a number of burials outside it. When the floor was re-laid above this (though the foundations themselves are still visible under the trapdoors below the carpet), the Frith Stool was brought out of seclusion and firmly cemented into position above the centre of the apse, on the assumption that this was the east end of Wilfrid's original church and therefore the site of his throne. It is now believed that the apse was in fact part of a small chapel, perhaps a mausoleum for saints and bishops, whose western end was under the later rood screen. Wilfrid's main church was further west, on the site of the present nave. There is, nevertheless, no intention to remove St Wilfrid's Throne from the honoured place it has occupied since 1910.