CASSS 19 Fragments and possible reconstruction

When the present nave was added to Hexham Abbey in 1907–8, many fragments of sculptured stone were built into its new walls or set in niches made for the purpose in the north aisle. These carved stones had turned up over the years, built into walls and stairs or buried in and around the church. Some were Roman, perhaps brought from Corbridge to decorate Wilfrid's church or to be copied by his craftsmen; some came from the mediæval priory and its graveyard. But many of these yellow-grey sandstone lumps remain from the Golden Age of Northumbrian Christianity, when the skilled craftsmen of Wilfrid's monastery shaped them to honour God and adorn His church.

CASSS 19 Fragments and possible reconstruction

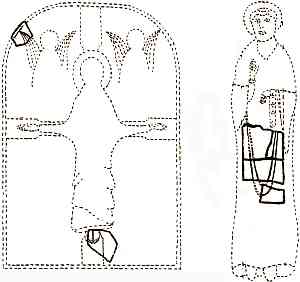

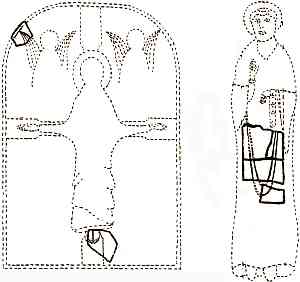

At the west end of the nave, prior to July 2014, two glass cases held fragments from a dolomite plaque found there in 1907. As arranged by Dr Harold Taylor, they show a crucifixion and an ecclesiastic. Currently these cases and their contents are in store, awaiting re-interpretation and a new display. The stone probably came from near Monkwearmouth, perhaps carved in the monastery there about 675–700, copying manuscripts. All the other Abbey fragments are of local sandstone.

Some of the stones were once part of the richly decorated building, fragments of frieze or pillar, screen or furnishing. Clearly, the walls and arches of Wilfrid's church carried colourful patterns and lively animal processions. Other stones originally stood nearby, as monumental crosses or as grave markers. All these show how the Northumbrian monks and craftsmen drew their inspiration from different traditions: there are interlace patterns of Celtic origin, writhing animal bodies in the Germanic style, vine-scrolls that came with Roman missionaries from the Mediterranean, and figure sculpture copied from Roman examples surviving at places like Corbridge. They show Anglo-Saxon sculptors copying patterns and devices from illuminated manuscripts or from ornamental metalwork like that found at Sutton Hoo.

When Wilfrid's abbey fell on hard times most of its carved stones disappeared. Many were broken up for use in other buildings, some were smashed by those who disliked their message. The few that survive are worn and weathered and have lost their colour, though several keep traces of paint. In our own times those rescued have been brought together to be studied and listed. More information can be found in Rosemary Cramp's Corpus of Anglo-Saxon Stone Sculpture, Vol I (CASSS), published by Oxford University Press for the British Academy in 1984. The pieces are numbered as there, with Professor Cramp's approximate dates and descriptions. Roman and late-mediæval stones are omitted, except for a few of doubtful date, while the two cross shafts, one in the South Transept, CASSS 01, and the other since October 2014 in the Monastic Workshop, CASSS 02, appear in Acca and Acca's Cross. Otherwise, most Anglo-Saxon stones are described, many in the new exhibition since October 2014, the rest in the Abbey.

The west wall of the Mercers' Gallery in the new Visitor Centre has eight (probably) Anglo-Saxon stones:

| 2. CASSS 21 is possibly Roman, a fragment of a richly carved classical screen (two other fragments are at Durham), its curling vine stem entangling the legs of one man and arm of another, a goat's head, and a cock. 3. CASSS 40 is the base of a pilaster of c675–720, with lines of cable moulding. |

CASSS 21 |

CASSS 40 |

| 4. CASSS 10 is a plain but elegant arm of a cross, c725. 6. CASSS 13 is a grave-marker cross with the name TVNDVINI, probably c775–875, found under Beaumont Street. |

CASSS 10 |

CASSS 13 |

| 7. CASSS 05 is the upper part of a cross-shaft, c900–1000, with neat interlace in a style found at Lindisfarne and Durham; it ends with the lower arm of the cross-head, whose interlace is better seen on the side facing the wall. 8. CASSS 12 is a corner of a cross-foot of c770–830, with neat spirals, leaves, and berries on two sides and the top. |

CASSS 05 |

CASSS 12 |

| 9. CASSS 38 is an impost of heavy interlace, c750–870. 11. CASSS 11 is a cross-head of c1000–1050; its two side arm are missing, but the upper and lower arms survive, with a prominent central boss. They have an aimless and confusing interlace. |

CASSS 38 |

CASSS 11 |

CASSS 33 |

CASSS 34 |

CASSS 20 |

Top-left CASSS 33 is a running cow or similar beast.

Bottom-left CASSS 34 is a lively running boar.

Right-hand side CASSS 20 is a fragment showing a fish head and part of its body.

Several Roman and Anglo-Saxon stone fragments were built into the west wall of the Nave when it was constructed in 1908:

| CASSS 28, in the left (south) and CASSS 29, in the right (north) corners of the west doorway are pieces of patterned frieze of c675–800. Both were in Wilfrid's church, though his builders may have re-used Roman friezes. |  CASSS 28 |

CASSS 29 |

| To the north of the west doorway, CASSS 14 is a cross-in-circle grave-marker from about 875–927. Further north along the west wall, CASSS 35 shows the hindquarters of a fine lion of about 700–750. Once it may have been part of a frieze or possibly an arm-rest for a stone seat. |

CASSS 14 |

CASSS 35 |

There are some Anglo-Saxon fragments in the niches in the north wall of the Nave. Counting outward, i.e. westward, from the crossing:

| The 2nd niche has CASSS 06, the upper part of a cross-shaft from c900–1000, well worn and carrying a tangled interlace in Lindisfarne tradition, with clearer, simpler patterns on the narrower sides. The 6th niche has CASSS 22, a rosette with thirteen compass-drawn petals around a twelve-petal centre, either Roman or a close copy of a Roman original. The 7th niche has CASSS 18, a massive post-conquest hogback. In the north chancel aisle, on a wooden plinth, CASSS 16 is a grave-cover of c925–1050, with a long-stemmed cross in relief; it is sometimes said to be Acca's, though Professor Cramp has suggested a later date. |

CASSS 22  CASSS 18  CASSS 16 |

CASSS 06 |

It has been said: “These dusty fragments are overcrowded and poorly displayed; but they are invaluable clues to visualizing the richly adorned and colourful interior that was once the glorious church of Wilfrid and Acca.” Some seventeen of them are now much better displayed in the new Visitor Centre; given time and necessary funding, the others will also be better conserved and re-displayed.